It probably won’t surprise anyone to learn that coffee sales are down as a result of the pandemic. Like makeup and gasoline, coffee is less in demand when people aren’t leaving their houses, and like the restaurant industry as a whole, coffee shops often rely on foot traffic or at the very least gathering indoors, both of which are currently discouraged. This is a good moment, as coffee is a little less present in our lives, to question why coffee is such a part of particularly American culture and whether it should be.

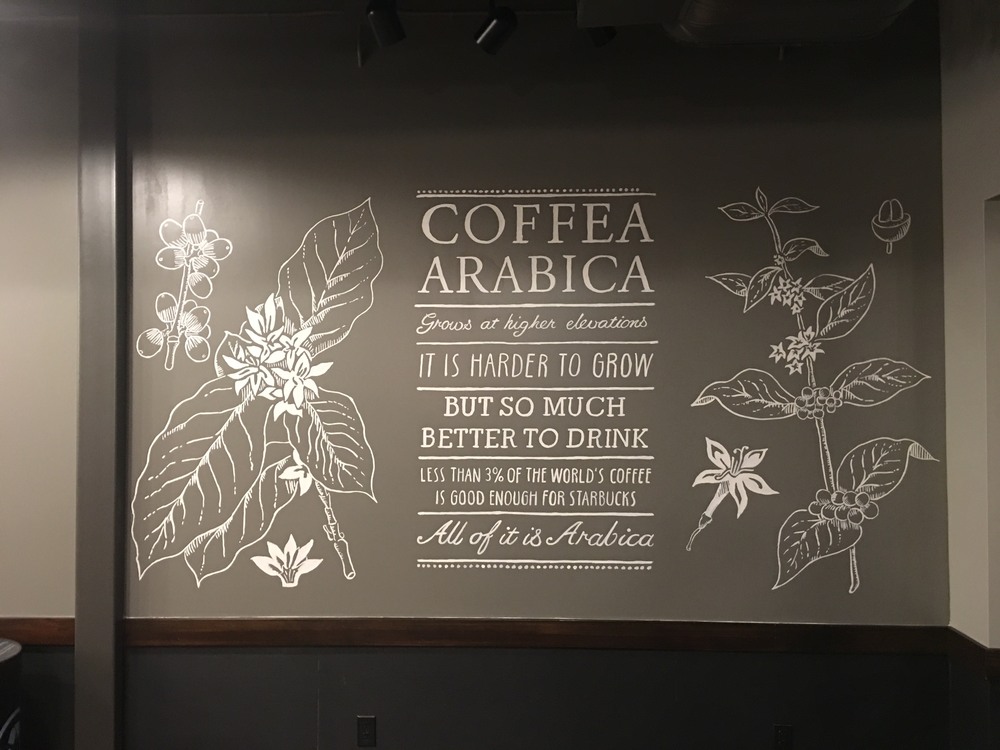

Coffee has conquered world culture in the modern era. The symbol of that is a Starbucks on every corner, but it’s even signaled in the names of coffee varieties. A coffee menu is a map of modern colonialism. The preferred bean, the arabica, is the start of coffee’s story of domination. Before the 17th century, coffee was the quintessential Arab drink, enjoyed throughout the Middle East and North Africa as an evening ritual, brewed heavy and thick with sugar. The English words for both of these derive from Arabic – qahwa and sukar. While sugar took Europe by storm as early as the eleventh century, coffee remained isolated to the Arab world until the rise of modern empires. It wasn’t just that European “expansion” made coffee available – coffee was a part of expansionist culture. When shipping companies sat down to garner loans to fund their trips, they did so in London’s coffeehouses. Before England was all about tea, it was all about coffee – a fact that is surprising to Americans given our snobbery for coffee, but we’ll get there.

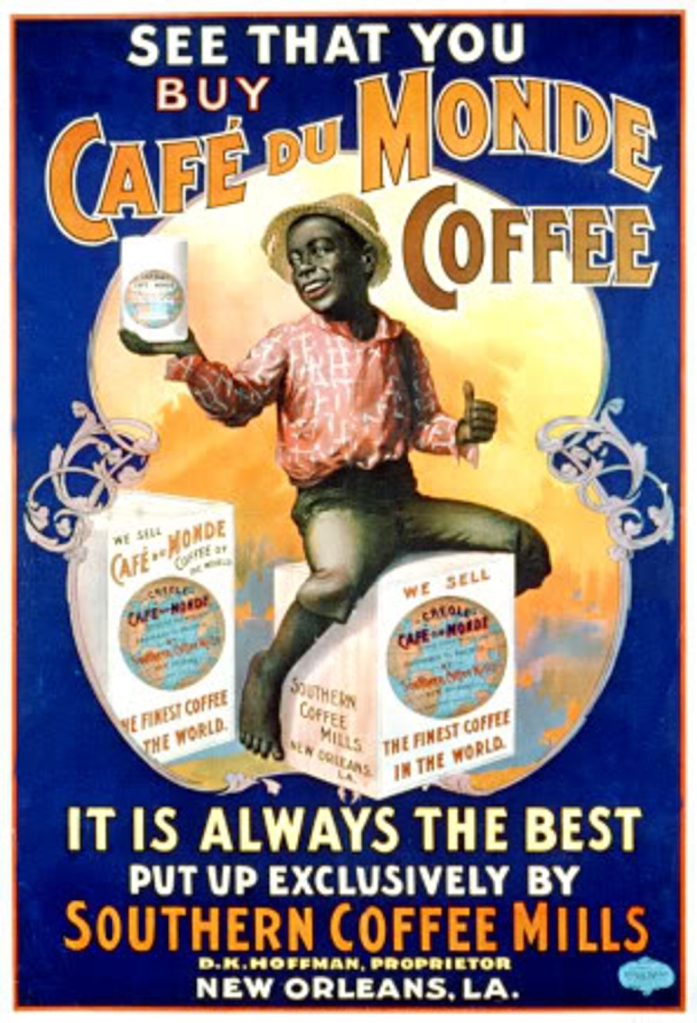

Like chocolate, tobacco, and, more recently, jazz and hot sauce, when Europeans decided to appreciate rather than abhor coffee, they also needed to take ownership of it. Coffee could not be an imported delicacy for Europe, it had to become something they produced themselves. They had to remove it from the hands of people they did not respect and refashion it into a culture they could find respectable and “civilized”.

Although European colonialism always had its sights set on Asia, over time empires like Portugal, Britain, Holland, and Spain realized that owning a chunk of the so-called Orient was more politically difficult and expensive than they had bargained for. So while these empires continued to play the long game in their efforts to secure pieces of South, Southeast, and East Asia, they found easier money in the Atlantic world. The most infamous example of this is the Atlantic slave trade and the sugar industry that supported it. But Europe’s economic involvement in all of the Americas was about making easy money through the exploitation of land and human labor. Again, we typically think of Cortez’s search for gold or cotton plantations in the American South. But all organized agriculture and mining was part of this exploitation.

So we return to the names of coffees. Have you had your Peruvian Blend today? As part of what is benignly referred to as the Columbian Exchange, European colonists brought coffee from Africa and the Middle East to South America, where they could more easily control its growth by creating an industrialized farming system around it. It is no coincidence that the flavors most sought-after by Europeans – coffee, chocolate, vanilla, cinnamon, and other spices – only grow in equatorial climates. These goods are at the nexus of European status symbols, in that they are foreign, difficult to cultivate, and feature prominently in cultures that Europeans have historically seen as “wild”. Farming these crops also meant dominating the peoples who tended them and the land on which they grew. European colonialism was most often directed at these climates, not because of some inherent developmental difference in the technologies or societies that live in cold vs hot climates, but because these climates support a biodiversity that Europeans could take as a status symbol.

But we need to note the difference between these goods that became European delicacies and the ones that were either looked down on or derided entirely. Some of the most iconic goods of the Columbian exchange – corn and potatoes – have in the modern world become synonymous with both the comfortable blandness of European and American food and European poverty. In contrast to coffee, these crops are characterized by how easy they are to grow, so they didn’t achieve the same kind of status, and instead were relegated to the monotony of peasant food. Even in this role they have been weaponized, as during the Irish potato famine, when Britain first limited Ireland’s food supply to potatoes and then refused to send aid when the blight hit. Meanwhile, peppers, which are also an easy crop to cultivate, were largely passed over by Europeans and instead have come to constitute a secret handshake of post-colonial peoples who were given the crop by Europeans and adopted its many spicy varieties as a point of cultural pride. But the most striking comparison is coca, which today is used medicinally in the Andes to fight altitude sickness, but was first taken by the descendants of Europeans in America as a consumer product – Coca-Cola – and then, when it was discovered to be addictive, dismissed as a dangerous drug and eventually criminalized. But consider that caffeine and cocaine are equally addictive, and that, in an odd parallel to coffee snobbery, coca has since split into the low-class crack and the high-class blow, allowing the descendants of Europeans to speak out of both sides of their mouths when it comes to the drug.

In the 20th century, coffee has both expanded its reach and refined its status. Each time coffee has become so ubiquitous as to be the drink of the working class, it has once again been coopted and made unattainable by the elite. Made wild again by cowboys, it was dignified to silver pots. Made a symbol of the Italian labor movement as espresso, it was turned on its head into fussy sophistication. And made into the drink that America runs on, it was turned into the most expensive daily habit of the aspirational middle class (but not, as many personal finance experts have asserted, the reason that young people can’t buy houses). In recent years, the cultural takeover of coffee via both McDonald’s and Starbucks has been so complete that their storefronts have adopted the social position once held by public libraries. After two black men were expelled without cause from a Philadelphia Starbucks, Starbucks instituted a corporate policy that customers need not make a purchase to sit in its stores or use its bathrooms. As a result, Starbucks locations have become public living rooms and bathrooms, hubs for free wifi and rest stops. They have taken on the association as a place where those without homes spend the day. And in quiet response, Starbucks has rolled out its higher-tier locations, the Starbucks Reserve. While Starbucks has capitalized on the universal popularity of its blended drinks, it has also capitalized on the backlash to these, the coffee snobbery movement. As consuming sugar has become synonymous with the diseases of the lower classes, being a true coffee drinker is now about drinking coffee black, and having discernment in the brewing method, water temperature, and of course geographical origin of the bean. We’ve come a long way from the syrupy drink that Bedouins were making over open fires.

In the trend of the wellness industry, coffee is on the road to becoming a health food. As with almost any food trend, this new outlook on coffee has little to do with the natural qualities of the bean, and more to do with who drinks it. As “quality” coffee increasingly becomes a marker of the moneyed class, health organizations are funding studies to show that a coffee habit isn’t bad for the body, and maybe is good for it. The same trend happened with chocolate in the mid-aughts. And while studies don’t show a link between coffee and any major diseases, we should still consider our national issue with sleep in light of how many cups of coffee we drink a day, not to mention what it does to our teeth.

Do we really want to give coffee this place in our society? Are we really comfortable with the normalization of a drug that controls our daily routines? Some of this isn’t coffee’s fault – there are bigger societal issues, like racial and wealth disparity that coffee habits just shine a light on – but coffee certainly is to blame for environmental harm, continuing global economic inequality, and daily quality of life health problems. Certainly we shouldn’t abandon coffee altogether, but maybe this is a good place to practice moderation on a society-wide scale.

I still drink at least two cups of coffee a day. I order mine from San Francisco Bay Coffee and usually order about three months worth at a time. It’s always super fresh and smells and taste amazing. I’m doing my part to keep coffee bean growers in business. Are you?!?! 🙂

LikeLike

I definitely am not, since I don’t drink coffee at all. No shame on those who do! But like everything we consume, we should be mindful about our demand for coffee.

LikeLike

This article is silly. People try to find evil and injustice in everything now it seems. Just let people enjoy their damn coffee. Despite what this article says, coffee, for most people, symbolizes nothing more than simple comfort and joy, which is much needed in these cruel times we’re living in. It makes people’s days and brings us together, much like a good meal. As far as I’m concerned, the past of coffee doesn’t matter. What it means now is all that matters, and it seems to bring far more happiness and financial prosperity than it does anything bad. This article is also stuffed with keywords and click bait. Just saying.

LikeLike

I respect that. I think a lot of people enjoy coffee, and there’s no reason they shouldn’t. I’m trying to shed light on why we shouldn’t take coffee for granted, and be thoughtful about how much we drink and why.

LikeLike

There was no potato famine. England just dumped them and left the Irish to starve.

LikeLike

There definitely was a potato blight, but it only became a famine because the English refused to send aid.

LikeLike

Are you kidding me????? Caffeine in coffee and tea is NOT as addictive as cocaine. Shame on you!

LikeLike

Hi Jennifer. As you can see from the medical study i linked over that text, caffeine and cocaine do in fact trigger the brain in the same way and even both cause withdrawal symptoms. The author of that study determined that caffeine was not a serious threat to health in the same way as cocaine because of the mildness of the response. Just because something is addictive doesn’t mean it is dangerous, but it should give us pause about making it a part of our daily lives.

LikeLike

Maybe I missed it, but in linking coffee to every evil known to modern man, it appears you somehow skipped over the toxic patriarchy.

LikeLike

I think I covered that under imperialism and cowboys

LikeLike

There were parts of the article that were interesting, and some that were untrue. Coffee drinking actually began in Africa. In a region of Ethiopia, called Kaffa (where we get the name coffee). Kaffa and Ethiopia in general have some of the most sought after coffee beans in the world to this day. There is a coffee ceremony that is done sometimes daily in many East African homes, and coffee has been drunk that way for generations. Coffee spread from the Horn of Africa to the Middle East, North to Europe and East to Asia. Europeans may have given one type of bean the name Arabica because they were intriduced to coffee, via the Arabs.

LikeLike

Excellent point! The African history of coffee was harder for me to get at, so i appreciate the correction!

LikeLike