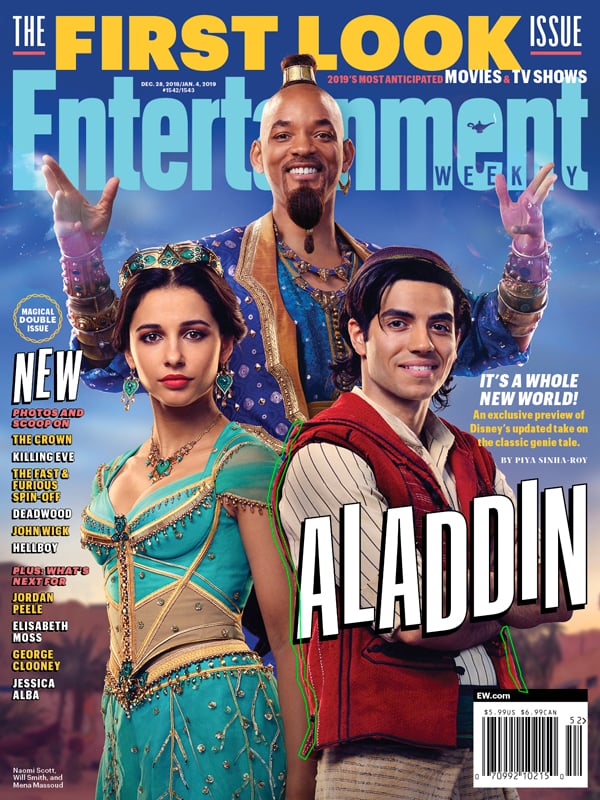

I’m not looking forward to this, but let’s be honest, I’ll probably end up seeing it anyway.

Oh hey, did you hear Disney is making a live-action version of its classic animated movie Aladdin? And the cast is all people of color? Wow, what a cool and progressive update on a favorite intellectual property!

The problem, though, is that this kind of update merely pays lip-service to representation, and is in itself problematic. While the original content has some dubious depictions of the Middle East and its peoples, it is ultimately a fantasy story and not intended to represent the real world, even though its visual tropes are based on historically racist imagery. By attempting to bring the story into the real world with the new movie’s casting, this new production applies what are no longer racist stereotypes to real people and gives these images renewed meaning. So although it’s a nice nod to acknowledge the problematic nature of Disney’s past films, updating the casting doesn’t do anything to improve the representation of Middle Eastern peoples the way that, say, creating a new movie based on Arab folklore or producing independent Middle Eastern films would. In fact, this update just brings offensive past visuals into the present.

But remaking Aladdin is pretty sensible for Disney. As the company has acquired Marvel and Star Wars, it’s been moving more toward live-action IP aimed at an older audience than for it’s golden age of animation films (although, let’s be honest, those movies are great at any age). The kids who grew up on those movies are now in their 20s and 30s and have some small amount of disposable income (insert funny joke about millennials being broke here), which for some reason they keep spending on nostalgic entertainment (insert second funny joke about millennials trying to capture their lost childhoods here). And because several of Disney’s classic movies have already had successful runs as Broadway shows, the company knows that these properties work in non-animated formats.

Coincidentally (wink wink) these are exactly the movies that are being updated for live-action: Beauty and the Beast, the Lion King, and Aladdin (and also the Jungle Book, but that’s another issue). All of these movies also passively deal with some current but not overly controversial social issue that will earn Disney lots of brownie points for bringing into the open. First it was feminist Belle. The Lion King was an easy update – just give it a predominantly black cast and people will applaud it for its efforts at representation – and then we don’t have to think too hard about the implications of making black people into African animals.

Aladdin is superficially the same deal – just make it a celebration of people of Middle Eastern descent! After all, it’s an Arab story, right? It comes from Arabian Nights, right? Disney should totally let this maligned group shine through a story from their own culture, just like they did with Moana, which went perfectly to plan and had no pushback whatsoever! Except Aladdin is way more complicated than that. And where there is already a precedent for the Lion King, where the Broadway show developed a secondary narrative about the advancement of African Americans, Disney is just dipping its toes into the murky waters of the representation of Middle Eastern peoples in the US, especially in a post-9/11 world.

The animated Aladdin came out in 1992, on the heels of the Gulf War, and some people have taken it as an attempt to “humanize the enemy“. I don’t particularly buy this explanation, especially because of one change the movie made between its original release and when the soundtrack and home video came out. In the opening song, “Arabian Nights”, the second line originally ran “where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face/ it’s barbaric, but, hey, it’s home” but was later changed to “where it’s flat and immense and the heat is intense/ it’s barbaric, but, hey it’s home”. But beyond this misstep, it’s critical to our impression of Aladdin that it does not depict a real place. I can’t stress this enough. Like Game of Thrones, the setting of Aladdin is explicitly fantastical, even though it has features that are reminiscent of, or even drawn from, the real world. This is a pretty major departure from most of the Disney animated canon, which is otherwise set in real places during specific historical periods with the addition of magical elements (Beauty and the Beast, The Emperor’s New Groove, Lilo and Stitch, Moana), or in the mythology of a real place with an implied real setting and vague time period (Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid, Frozen, Hercules). The Lion King is another major departure in that sense, except that it’s clearly set in Africa and grounded in real ecology, rather than history or mythology, which makes sense because it’s about animals, not people. But Aladdin is set in a strange amalgam of vaguely “eastern” places. Its palace kind of looks like the Taj Mahal. People wear clothes that are maybe kind of like what Egyptians were wearing around the turn of the century.

Everyone has a generally “Arab-ish” look – medium-toned skin, dark hair, dark eyes, thick eyebrows. And people carry scimitars, which is, I guess, kind of a reference to the historical Levant? There are a few verbal clues in the movie, like the fruits they sell in the marketplace (sugared dates, figs, and apricots), or the fact that the names all sound vaguely Arab, even when they are nonsense (the monkey’s name, Abu, would mean “father” in Arabic if there were another word after it, but as it is it’s kind of nonsense). And then there’s the name of the kingdom, Agrabah, which has the cadence of an Arabic word but it also nonsense.

So you might think that these elements that make the setting of Aladdin ambiguous are just taken from its source text. Yes and no. There is a story that is often included in the 1001 Nights anthology that is either called Aladdin or that has a main character with that name, and it has a vaguely similar plot to the Disney movie, in that it is about a beggar boy who falls in love with the princess when he illegally watches her walking to the bath one day, and he then wishes to be made into a lord, which has absolutely no repercussions. Every other detail in the story was added through other media, most notably the 1940 movie The Thief of Baghdad (and the 1924 version), which is not explicitly the Aladdin story but has a lot of similar details. Interestingly, the villain, Jaffar, was not supposed to be a villain until Conrad Veidt was cast in the role, because he had a reputation for playing the villain. I also think it’s worth throwing in the possible influence of the 1989 NES game Prince of Persia, which is remarkably similar to the 1992 Disney movie. In these renditions, the Aladdin story is consistently an ambiguous Middle Eastern story, with a fantastical setting and vague details. So it makes zero sense to cast a movie with such a setting using actors with any particular background for “authenticity” because there is no place to be authentic to.

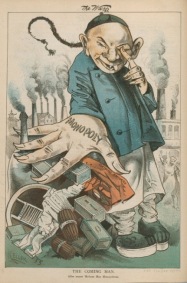

There is a word for this, and it is Orientalism (now that I’ve started writing posts about Orientalism, you will literally never get me to stop). Orientalist fantasies imagine a nonspecific eastern setting filled with riches and sexy women, in which a heroic (often white) young protagonist must brave the natural dangers of the landscape as well as the treacherous people.

This trope is a massive one, spanning hundreds of years across literature, paintings, movies, comic books, fashion – you name it. Orientalism really developed in the 18th century, as Europe felt an immense military and commercial threat from the Ottoman Empire. In a way, the expansiveness of the Ottoman territories justifies mushing together so many regions, but Orientalism came to encompass a generalized anxiety about other Asian powers as well, including the burgeoning restored Japanese empire and a seemingly impenetrable China.

The anthology known as 1001 Nights (in Arabic الف ليلة وليلة or “Alf Layla wa Layla) is a bit of a microcosm of Orientalism itself. The frame story tells of a woman named Sheherezad who is forced to marry a murderous king and saves herself by telling him stories that all end on a cliffhanger and just lead to another story – this frame is believed to have originated in India early in the first millennium. But the rest of the stories, thanks to their loose organization, are collections from a wide geography, some of which likely formed together thanks to trade connections across western and southern Asia or perhaps due to the reach of Islam and the connections it fostered. But this organic collection is not the set of stories we now know. Those were put together by a few enterprising Europeans in the 18th century, who translated parts of the collections they found, and then changed the stories or concocted new ones to fill out the collection. Some of the most famous stories – Aladdin, Sinbad, Ali Baba – were entirely invented by these European collectors. The anthologies became popular throughout Europe, and, ironically, made their way back to the Middle East where they were translated back into Arabic. So, while there is a sort of genuine, “authentic” 1001 Nights, in that there are some incomplete medieval compilations that have some of these stories, this collection is by definition a set of stories that shifted as it moved across a massive geography and many languages. It is certainly legitimate to consider the stories written by Europeans as part of the current canon of 1001 Nights, since they really have been adopted into it. But they don’t reflect Arabic culture or folklore. Moreover, the appeal of these stories worldwide was in their cultural vagueness, rather than their authenticity. It’s because they are fantastical and only broadly Asian that they have been accessible to so many audiences. There is a sort of “genuine” Arabic story anthology, which is Kalilah wa Dimna, another frame story with folktales, most of them about animals. But this anthology is not nearly as accessible – in some ways, it’s too culturally specific to allow the audience to imprint its own imagination on the stories.

That imagination is key when it comes to the continued popularity of stories like Aladdin and their vaguely Middle Eastern setting. Because the audience can fit the story to its own mental image of this setting, because the audience expects a particular set of visual or story tropes, they are willing to accept something that is otherwise very foreign. Think about Game of Thrones again – when it first aired, the selling point was that it wasn’t overtly magical for the most part, but was instead just a really compelling political drama. The fantasy elements on top of the medieval-ish setting would have been too distractingly different for an audience that had already gotten tired of Lord of the Rings.

In the same way, the stories in 1001 Nights are just enough outside of the types of stories that, say, American audiences are used to that they need something that makes them familiar. The audience doesn’t want to experience culture shock sitting in a movie theater, or at least not in a big-budget film. If there’s going to be a genie (a “jinn” in Islamic folklore), an all-powerful being that lives on a different plane of existence, he’s got to be friendly and sing songs, because otherwise that’s just plain terrifying. Never mind that the jinn are a crucial part of the Islamic ordering of the universe, on par with humans and angels, and that they are morally pretty much chaotic neutral (I would link to something on this, but Wikipedia isn’t so great in this instance and a lot of the websites about Islam are … not great). Similarly, Aladdin and other such stories are typically presented as simple romances or adventures, rather than stories about ethically dubious people outsmarting other equally ethically dubious people. These are cultural reference points that don’t really make sense in the broader American context, even if there are substantial subcultures that would appreciate them.

So attempting to “update” Aladdin by using it as a vehicle for Middle Eastern representation kind of misses the point. This isn’t one of their stories that needs authentic voices to tell. It’s an amalgam of many different cultures across a really massive time period. It sits in a strange grey area of cultural appropriation – it doesn’t belong to anyone, so it’s not clear what’s being appropriated, but there are definitely elements of the story that are kind of racist in their representation. For instance, the look of the genie is largely based on turn of the century impressions of Chinese people (note the top knot and eyebrows).  Maybe it’s those kinds of visual features that really need an update – at least they covered Jasmine’s torso. But on the whole, I think it’s ok to enjoy this kind of setting – it’s taken on a life of its own that reflects American culture just as much as pre-modern Middle Eastern culture, but importantly, it has lost the context of a cultural clash that gave this kind of imagery political power.

Maybe it’s those kinds of visual features that really need an update – at least they covered Jasmine’s torso. But on the whole, I think it’s ok to enjoy this kind of setting – it’s taken on a life of its own that reflects American culture just as much as pre-modern Middle Eastern culture, but importantly, it has lost the context of a cultural clash that gave this kind of imagery political power.

In a similar vein, bellydance, which has roots in traditional Middle Eastern dance but was sexualized by Europeans in the 19th century, has been reclaimed by Middle Eastern women as a new part of their culture. The political anxieties that gave birth to hypersexualized images of Arab women don’t exist anymore – if anything, they’ve been replaced with the opposite image. In this context, bellydance is modern and empowering, while still feeling Middle Eastern both to the women who do it and the wider audience. In the same way, we have new symbols of American anxieties about the Middle East now, and those are a whole other problem to worry about. But where we should know better in 2018 is not to inject new political meaning into this imagery by making it about reclaiming a folktale for “it’s own people”. We should certainly be using every opportunity for more diverse representation in popular media, but we should absolutely not be justifying it only as some kind of superficial reparation. When we make these kinds of superficial gestures, we justify Orientalism – we make it acceptable.

I think it’s easy to get really excited about the idea of doing something to further equality without giving too much thought to whether the gesture actually means something. Especially in the wake of such a long history of Hollywood white washing, even the sleepiest of woke audiences is enthusiastic about diversifying media and telling a broader range of stories. But some stories haven’t been whitewashed, because they were never authentically anything to begin with. At the risk of alienating a lot of people, I use Avatar: The Last Airbender as an example of this. As much as I love Avatar, it’s not a product of any Asian culture – it’s explicitly a hodge-podge of Asian stuff, in homage to anime, kung fu movies, and Confucianism. The original voice cast was largely white. And yet when it was made into a live-action movie, suddenly the biggest issue, to trump even the fact that it was just a bad movie, was that the boy playing Aang was white. I ask genuinely: would it have been better to cast a boy of some ambiguously Asian background (ideally Tibetan, since the Air Nomads seem like a stand-in for Tibetans) to play a magical boy who can fly in this fictional world? Or would it have come off as a strange minstrel show? This, I think, is the choice we are demanding when we insist on authentic depictions in stories that are not themselves authentic. If we want to elevate the voices of the underrepresented, we should be seeing movies actually made by Arabs, of which there are many. But they are generally not happy nor do they have singing magicians, because of the 20th century in the Middle East. So, I say it’s fine to enjoy Aladdin, live action or animated, as long as you recognize what it is and what it’s not, and maybe we should all consider some more meaningful ways to increase diversity in media representation.

[…] Eastern. It would have made sense, then, to toss anything that seemed too mystical into the camp of the fearful “Orient” and be done with it. Alchemists who felt a change was in order decided to wipe the slate clean and […]

LikeLike